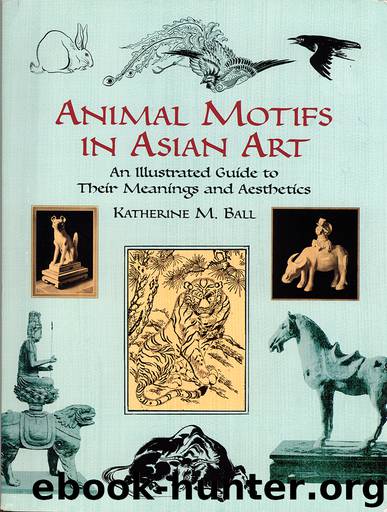

Animal Motifs in Asian Art by Katherine M. Ball

Author:Katherine M. Ball [M. Ball Katherine]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Dover Publications

Published: 2014-03-17T04:00:00+00:00

From a coloured woodcut by Yeizan. Not Foxes

The Fox’s Wedding—like the Mouse’s Wedding, shown in an accompanying illustration, entitled, “The Dream,” by Toyokuni—is, after all, one of the many instances in which the prolific imagination of the Japanese people led them to confer upon animals human customs. Japanese weddings always take place in the evening, because night represents the negative principle of In, while the participants represent the positive principle of yō—the condition of In-yō being a necessity for a happy marriage. The fox, however, representing the In, must marry during the day, but since he mainly haunts dark places, particularly avoiding the sun, the great yō symbol, he selects for his wedding a time when it is partially obscured by a rain.

In the beautiful design by Hokusai, the wedding procession is dimly shown in the middle distance; in the painting by Shoūn, a nearer view is depicted; while in the woodcut by Minkō a closer view of the bride in the norimono, “sedan chair,” may be seen; and in the print by Suiyō, the first-born is being taken to the temple.

The fox is honoured as the messenger of Inari Daimyōjin, the presiding genius of the temples of Mount Inari—noted for its unusual growth of rice—located near Fushimi, in the vicinity of Kyōto. Concerning this deity there is much confusion. Some authorities claim that Uga no Mitama, the Shintō goddess of crops, including rice, has this distinction, for the word Inari means rice-bearing; ina, “rice,” and ri, a homophone of ne, “package.” Others maintain that Inari Daimyōjin is none other than Inari Sama, also called Ojisan, a being who, appearing to Kōbō Daishi on the hills back of Inari-yama, was adopted by the great founder of the Shingon sect as the protector of the temple. But the INARI CHINZA YURAI states that this old man—which Hokusai, in the accompanying woodcut, has represented as “an ancient of days “carrying rice sheaves—was only a mere mortal by the name of Ryūzuda, who lived at the foot of the mountain, and spent his days cultivating the ricefields and his evenings chopping wood.

This work further suggests that the old man may have been the spirit of the mountain, but he never could have been a manifestation of the Goddess of the Harvest, the Divine Mother, or Earth, which yields fruits to nourish and sustain mankind.

The association of the fox with the rice-goddess is said to be due to a misunderstanding of names, the significance of which is derived from another homophone. Uga no Mitama had a second name, Miketsu no Kami. The two first characters of this name, Mike and tsu, when transposed into mi and ketsu, suggest two other characters, me ketsu, meaning “three foxes.” Upon such slender threads hang the symbols of mankind. The fox thus came to be identified with the goddess, but only as a messenger and attendant of the temple, hence two foxes, such as are shown in given illustrations, guard all Inari shrines. Notwithstanding this explanation, Inari or

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18635)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5479)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3677)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3547)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3533)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3457)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3363)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3326)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3183)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2922)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2919)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2885)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2729)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2724)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2674)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2643)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2588)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2581)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2516)